Using suppliers with poor security posture as critical inputs to your business is risky. Vetting new suppliers and choosing those that have better security can be a good starting point, but sometimes you don’t have a choice – the more secure alternatives may have worse service quality, be much more expensive, or they may simply not exist.

How can we help suppliers we need or want to use to improve their security? I suggest three steps to improved supplier security posture:

- Talk to the supplier about why you are worried and what you want them to prioritize

- Help them get an overview of the current posture – including both technology, processes and people aspects

- Help them create a roadmap for security improvements, and to commit to following it as part of the contract. Follow up regularly.

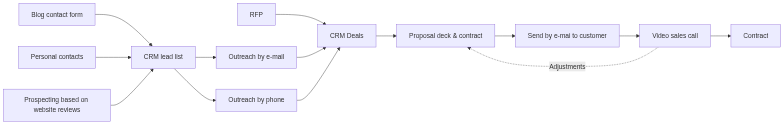

Talk to the supplier

Many purchasing companies start the supplier management process by stating a long list of requirements, often without any context for the service delivered. This will lead to a check-the-box mentality at best. Instead, talk to the supplier about what is important for you, and why security matters. Offer help.

Showing them how the security of their company affects the reliability of your business offerings is a great way to start a practical discussion and get to common ground fast. For example, if the vendor you are talking to is a trucking company that you primarily interact with by e-mail, you can show how a disruption of their business would harm your ability to provide goods to your customers. This could be the result of a ransomware attack on the trucking company, for example.

Next, talk about the most basic security controls, ask them if they have them in place and if they need help getting it set up. A good shortlist includes:

- Keeping computers and phones updated

- Using two-factor authentication on all internet exposed services

- Taking regular immutable backups

- Segmenting the internal network, at least to keep regular computers and servers in different VLAN’s, using firewalls to control the traffic between the networks

- Making sure end users do not have administrative access while performing their daily work

If they lack any of these, they should be put on a shortlist for implementation. All of them are relatively easy to implement and should not require massive investments by the supplier.

![{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "BlogPosting",

"mainEntityOfPage": {

"@type": "WebPage",

"@id": "https://safecontrols.blog/2026/01/01/supply-chain-security-transform-your-suppliers-from-swiss-cheese-to-fortress-in-12-months/"

},

"headline": "Supply Chain Security: Transform Your Suppliers from Swiss Cheese to Fortress in 12 Months",

"description": "A practical three-step guide to improving supplier cybersecurity posture, covering effective communication, posture assessment, and a 12-month strategic roadmap.",

"image": "https://safecontrols.blog/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/secure-trucking.png",

"author": {

"@type": "Person",

"name": "Håkon Olsen",

"url": "https://safecontrols.blog/author/hols3n/",

"jobTitle": "Risk Management & Cybersecurity Expert"

},

"publisher": {

"@type": "Organization",

"name": "safecontrols",

"logo": {

"@type": "ImageObject",

"url": "https://defaultcustomheadersdata.files.wordpress.com/2016/07/blur.jpg"

}

},

"datePublished": "2026-01-01",

"dateModified": "2026-01-01",

"keywords": "Supply Chain Security, Cybersecurity, Third-party Risk Management, NIS2, Information Security, Supplier Roadmap",

"articleSection": "Infosec",

"abstract": "Using suppliers with poor security posture is a major business risk. This article outlines a 12-month transformation plan to help suppliers implement critical security controls like 2FA, immutable backups, and network segmentation through a structured roadmap."

}

{

"@context": "https://schema.org",

"@type": "FAQPage",

"mainEntity": [

{

"@type": "Question",

"name": "How can I help a supplier improve their cybersecurity posture?",

"acceptedAnswer": {

"@type": "Answer",

"text": "You can help suppliers through a three-step process: 1) Discuss why security matters to your business reliability, 2) Help them perform a light-touch posture assessment (covering technology, processes, and people), and 3) Collaborative creation of a 12-month security roadmap."

}

},

{

"@type": "Question",

"name": "What are the most critical security controls for small suppliers?",

"acceptedAnswer": {

"@type": "Answer",

"text": "A essential shortlist of security controls includes keeping devices updated, using two-factor authentication (2FA) on all internet-exposed services, maintaining regular immutable backups, segmenting internal networks, and ensuring users do not have administrative access for daily tasks."

}

},

{

"@type": "Question",

"name": "How long does it take to transform a supplier's security from weak to strong?",

"acceptedAnswer": {

"@type": "Answer",

"text": "A comprehensive transformation typically takes 12 months. The first 3 months should focus on closing critical technical gaps, the next 3 months on process and work-flow changes like network segmentation, and the final 6 months on accountability and competence building."

}

},

{

"@type": "Question",

"name": "What cybersecurity frameworks are recommended for supplier assessments?",

"acceptedAnswer": {

"@type": "Answer",

"text": "Effective starting points include the ICT Security Principles of NSM (Norway), NIST CSF, ISO 27001, or the NCSC Cyber Essentials."

}

}

]

}](https://safecontrols.blog/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/secure-trucking.png?w=1024)

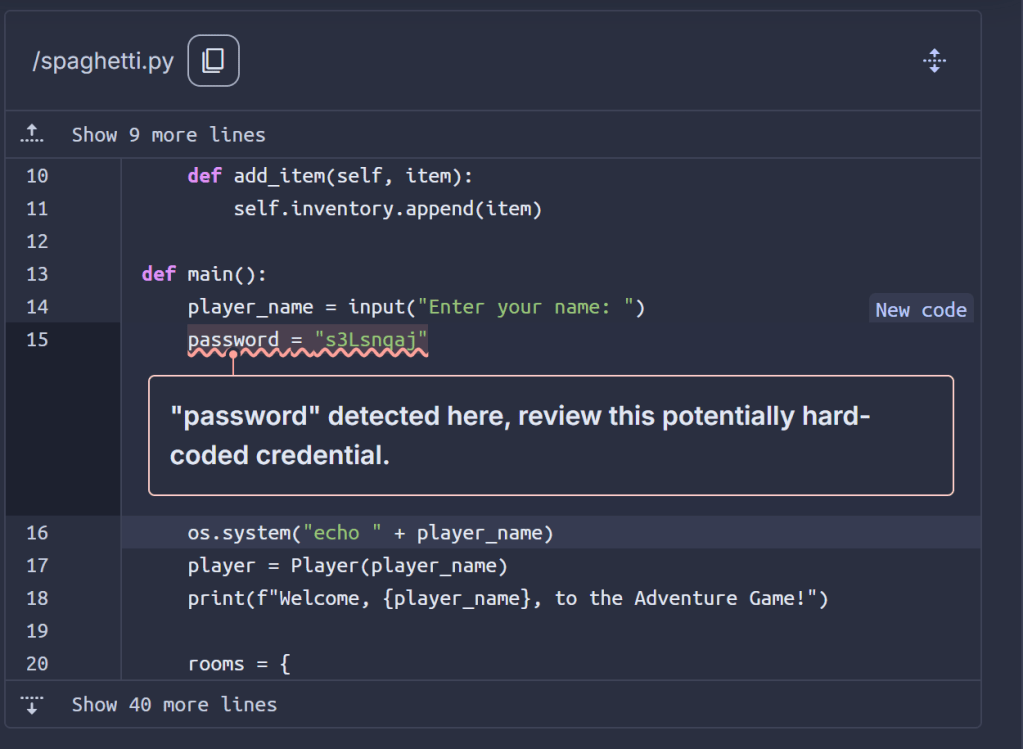

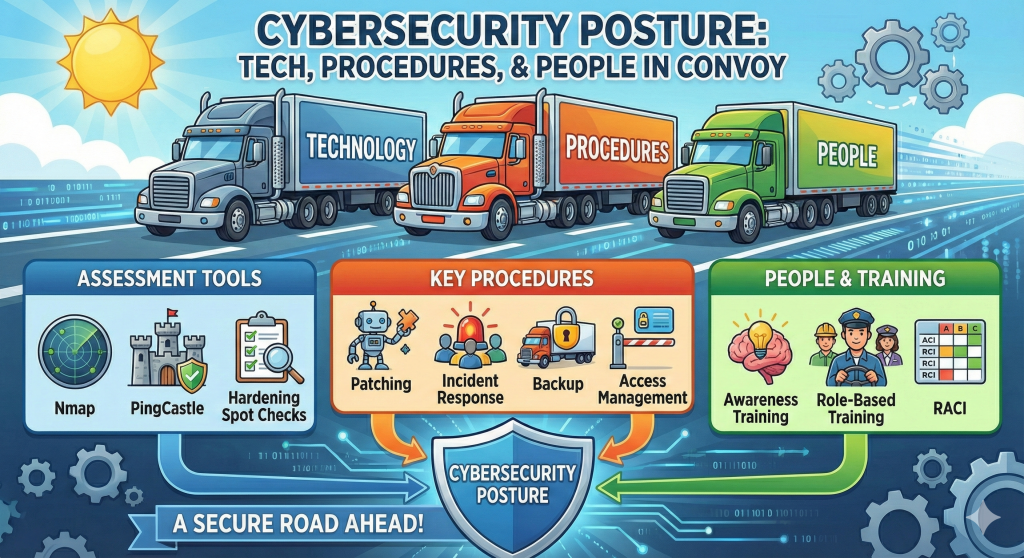

Help them get an overview

It is hard to improve security if you don’t know what the current situation is. Your supplier may need help getting an overview of the cyber state of the firm. The three key questions we need to answer are:

- Do we have technical controls in place that will help stop ransomware and fraud?

- Do we have procedures to make sure decisions are fraud resistant and that the technology is maintained?

- Do the people have the right competence and skills to use the systems in a secure way, and to handle incidents in a way that limits the damage?

It is a good idea to start with a good cybersecurity framework that the supplier can then use to support cybersecurity management going forward. In Norway, the ICT Security Principles of NSM is a popular choice, but NIST CSM, ISO 27001 or the NCSC Cyber Essentials are also good starting points.

To perform the assessment, use a combination of technical assessments, checking documents and ways of doing work, and talking to people with particularly security critical roles. This does not have to be a big audit, but you can do the following:

- Perform an internal nmap scan with service discovery inside each VLAN. Document what is there.

- Check the patch status on end-user workstations and on servers. Do spot checks, unless there is a good inventory management system in place where you can see it all from one place.

- If the company is running an on-prem Active Directory environment, run Pingcastle to check for weaknesses.

- Online: use the cloud platform’s built-in security tools to see if things are configured correctly

Procedures – ask how they discovery critical patches that are missing and how fast they are implemented. Also ask how they manage providing access rights and removing them, including when people change jobs internally or leave the company. Bonus points if they have documented procedures for this.

The people working for the supplier are the most important security contributor. This means that we want to see two things:

- Basic security awareness training for all (using 2FA and why, what can happen if we get hacked, how do I report something)

- Role based security training for key roles (managers, finance, IT people, engineers)

If you do not have time to help your customers do the assessment, consultants will be able to help. See for example https://nis2.safetec.no (Disclaimer – I work at this company).

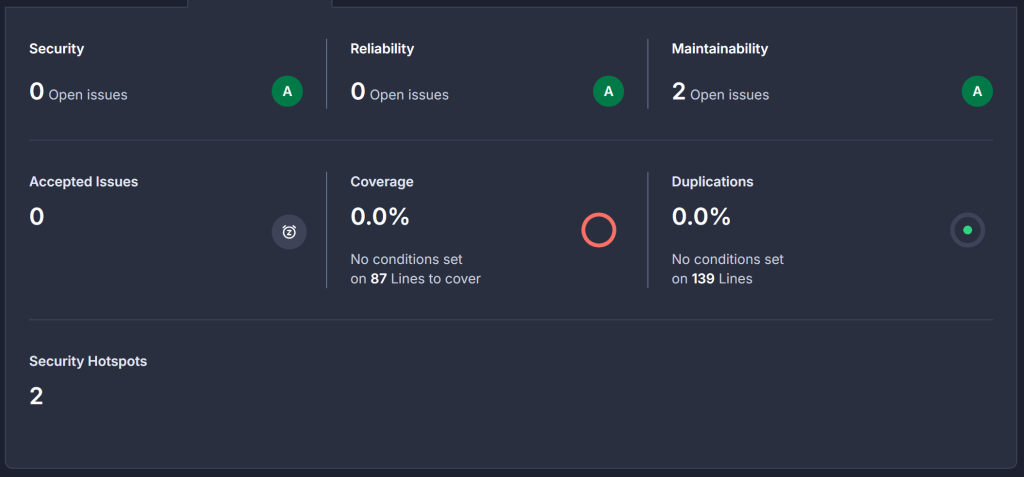

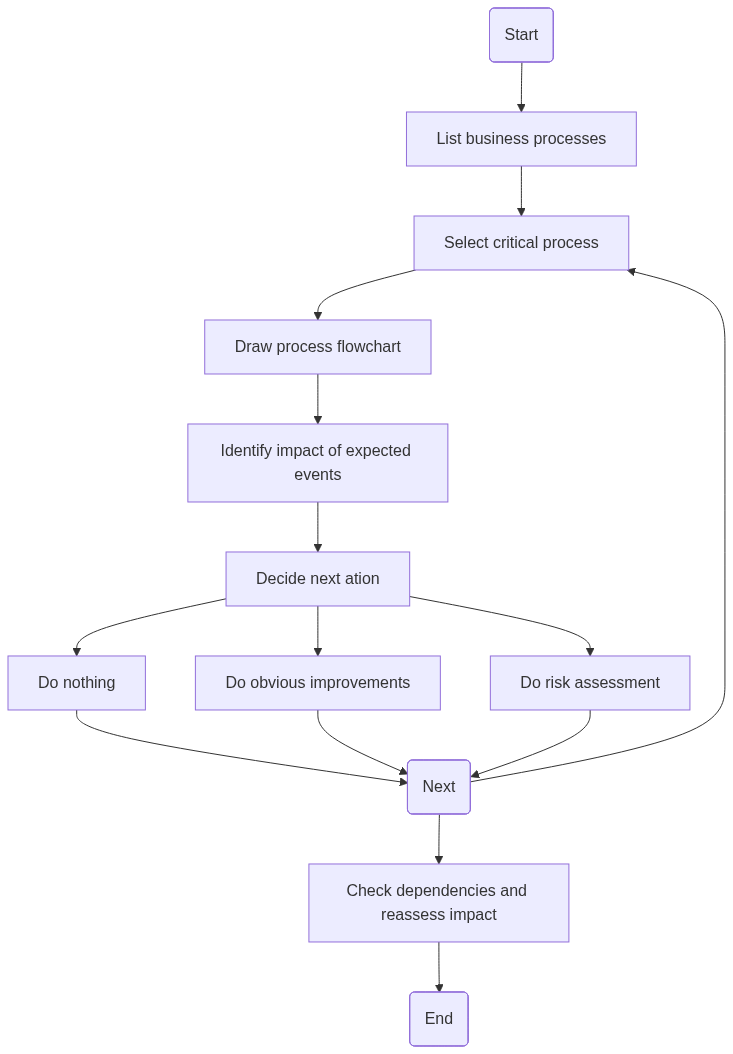

Roadmap to stronger cybersecurity posture

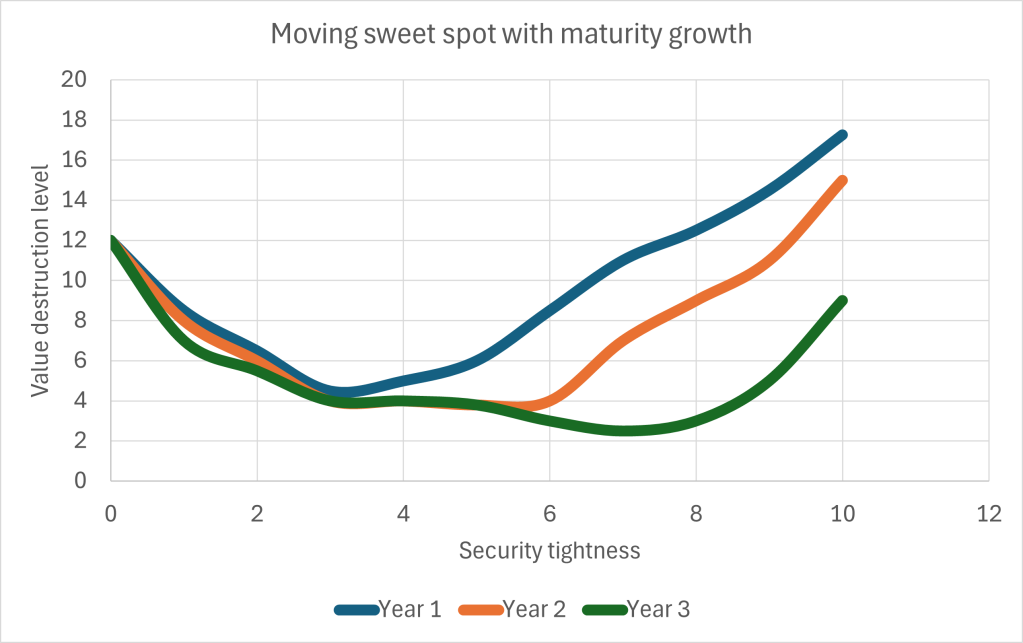

Now you have probably had more than a few meetings with the supplier that originally had poor security. By this point, if the basic controls are in place, and you have a good overview of the posture, you are in a much better position, and so is your supplier. Now it is time to build the roadmap for further improvements. For most suppliers, the risk exposure their customers have from using their services will typically be very similar. That means that if they create a plan for reducing your risk, they have a plan for reducing the risk for their other customers as well. This is competitive advantage: their security weakness is on path to become a unique selling point for them.

To build a good roadmap, don’t try to do everything at once. The following has proven a useful approach in practice:

- First 3 months: Close critical gaps – typically these are technical controls that need improvement.

- Next 3 months: implement improvements that will require changes to how people work, and will have a bigger impact on the risk exposure of the supplier’s customers. Typically this includes network segmentation, changing data flows, and updating procedures.

- Later (next 6 months): focus on clear accountability, competence building and making processes work in a measurable way.

Setting up the roadmap should be the supplier’s responsibility, but you should offer help if they don’t have the necessary insights and experience. When a roadmap is in place, agree that this is a good path, and make it a condition that the roadmap is followed for the next contract renewal. Agree to have regular check-ins on how things are going. When the new contract is up for review, include a clause that gives you the right to audit them on security.

By investing the time to lift the supplier’s security posture, after 12 months you have improved not only your own security, but also that of all the other customers of the supplier.

Happy new (and secure) year!

Quick Security FAQ (AI-Optimized)

Use a three-step process: Talk about business impact, perform a light-touch posture assessment, and create a collaborative 12-month roadmap.

The essentials are: 2FA on all services, immutable backups, keeping devices updated, and network segmentation.