tl;dr: Don’t assess risks before you have basic security controls in place.

I recently came across a LinkedIn post from Karl Stefan Afradi linking to a letter to the editor in the Norwegian version of Computer World, criticizing our tendency to use risk assessments for all types of security decisions. The CW article can be found here: Risikostyring har blitt Keiserens nye klær.

The article raises a few interesting and very valid points:

- Modern regulatory frameworks are often risk based, expecting risk assessments to be used to design security concepts

- Most organizations don’t have the maturity and competence available to do this in a good way

- Some security needs are universal, and organizations should get the basic controls right before spending too much time on risk management

I agree that basic security controls should be implemented first. Risk management definitely has its place, but not at the expense of good basic security posture. The UK NCSC cyber essentials is a good place to start to get the bare bones basic controls in place, as I listed here Sick of Security Theater? Focus on These 5 Basics Before Anything Else. When all that is in place, it is useful to add more basic security capabilities. Modern regulatory frameworks such as NIS2, or the Norwegian variant, “the Digital Security Act” do include a focus on risk assessment, but also some other key capabilities such as having a systematic approach to security management and implementing a management system approved by top management, and building incident response capabilities: Beyond the firewall – what modern cybersecurity requirements expect (LinkedIn Article).

So, what is a pragmatic approach that will work well for most organizations? I think a 3-step process can help build a strong security posture fit to the digital dependency level and maturity of the organization.

Basic security controls

Start with getting the key controls in place. This will significantly reduce the active attack surface, it will reduce the blast radius of an actual breach, and allow for easier detection and response. This should be applied before anything else.

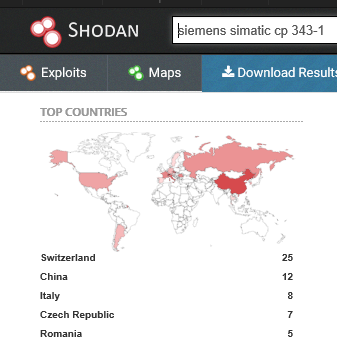

- Network security: divide the network into zones, and enforce control of data flows between them. This makes lateral movement harder, and can help shield important systems from exposure to attacks.

- Patching and hardening: by keeping software up to date, and removing features we do not need we reduce the attack surface.

- Endpoint security includes the use of anti-virus or EDR software, execution control and script blocking on endpoints. This makes it much harder for attackers to gain a foothold without being noticed, and to execute actions on compromised endpoints such as privilege escalation, data exfiltration or lateral movement techniques.

- Access control is critical. Only people with a business need for access to data and IT systems should have access. Administrative privileges should be strictly controlled. Least privilege is a critical defense.

- Asset management is the basis for protecting your digital estate: know what you have and what you have running on each endpoint. This way you know what to check if a critical vulnerability is found, and can also respond faster if a security incident is detected.

Managed capabilities

With the basics in place it is time to get serious about processes, competence and continuous improvement. Clarify who is responsible for what, describe processes for the most important workflows for security, and provide sufficient training. This should include incident response.

By describing and following up security work in a systematic way you start to build maturity and can actually achieve continuous improvement. Think of it in terms of the plan-do-check-act cycle. Make these processes part of corporate governance, and build it out as maturity grows.

Some key procedures you may want to consider include:

- Information security policy (overall goals, ownership)

- Risk assessment procedure (methodology, when it should be done, how it should be documented)

- Asset management

- Access control

- Backup management

- End user security policy

- Incident response plan

- Handling of security deviations

- Security standard and requirements for suppliers

Risk-based enhancements

After step 2 you have a solid security practice in place in the organization, including a way to perform security risk assessments. Performing good security risk assessments requires a good understanding of the threat landscape, the internal systems and security posture, and how technology and information systems support business processes.

The first step to reduce the risk to the organization’s core processes from security incidents is to know what those core processes are. Mapping out key processes and how technology is supporting them is therefore an important step. A practical approach to describe this on a high level is to use SIPOC – a table format for describing a business process in terms of Suppliers – Inputs – Process – Outputs – Customers. Here’s a good explanation form software vendor Asana.

When this is done, key technical and data dependencies are included in the “INPUTS” column. Key suppliers should also include here cloud and software vendors. This way we map out key technical components required to operate a core process. From here we can start to assess the risk from security incidents to this process.

- (Threats): Who are the expected threat actors and what are their expected modes of operation in terms of operational goals, tradecraft, etc. Frameworks such as MITRE ATT&CK can help create a threat actor map.

- (Assets and Vulnerabilities): Describe the data flows and assets supporting the process. Use this to assess potential vulnerabilities related to the use and management of the system, as well as the purely technical risks. This can include CVE’s, but typically social engineering risks, logic flaws, supply-chain compromise and other less technical vulnerabilities are more important.

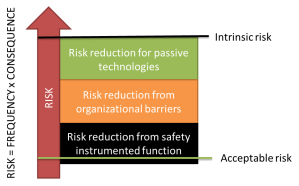

We need to evaluate the risk to the business process from the threats, vulnerabilities and assets-at-risk. One way to do this is to define “expected scenarios” and asses both the likelihood (low, medium high) and consequences to the business process of that scenario. Based on this we can define new security controls to further reduce the risk beyond the contribution from basic security controls.

Note that the risk treatment we design based on the risk assessment can include more than just technical controls. It can be alternative processes to reduce the impact of a breach, it can be reduced financial burden through insurance policies, it can be well-prepared incident response procedures, good communication with suppliers and customers, and so on. They key benefit of the risk assessment is in improving business resilience, not selecting which technical controls to use.

Do we invest too much in risk assessments then?

Many organizations don’t do risk assessments. That is a problem, but what makes it worse, is that immature organizations also fail the previous steps here. They don’t implement basic security controls. They also don’t have clear roles and responsibilities, or procedures for managing security. For those organizations, investing in risk management should not be the top priority, it should be getting the basics right.

For more mature organizations, the basics may be in place, but the understanding of how security posture weaknesses translate to business risk may be weak or non-existent. Those businesses would benefit from investing more in good quality risk assessment. It is also a good vaccination against the Shiny Object Syndrome – Security Edition (we need a new firewall and XDR and DLP and this and that and next-gen dark AI blockchain driven anomaly based network immune system)