Welcome to your personal AI Kitchen! In today’s fast-paced business world, time is your most precious ingredient, and Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools are the revolutionary kitchen gadgets you didn’t know you needed. Just like a great chef uses precise instructions to create a culinary masterpiece, mastering the art of “prompt engineering” for AI is your secret to unlocking unparalleled efficiency and supercharging your learning journey with generative AI.

Inspired by the “AI Prompt Cookbook for Busy Business People,” let’s dive into how you can whip up amazing results with AI for business.

The Secret Ingredients: Mastering the Art of AI Prompting

Think of your AI tool as an incredibly smart assistant, often powered by Large Language Models (LLMs). The instructions you give it – your “AI prompts” – are like detailed recipe cards. The better your recipe, the better the AI’s “dish” will be. The “AI Cookbook” highlights four core principles for crafting effective AI prompts:

Clarity (The Well-Defined Dish): Be specific, not vague. When writing AI prompts, tell the AI exactly what you want, leaving no room for misinterpretation. If you want a concise definition of a complex topic, specify the length and target audience for optimal AI efficiency.

Context (Setting the Table): Provide background information. Who is the email for? What is the situation? The more context you give in your AI prompt, the better the AI understands the bigger picture and tailors its response, leading to smarter AI solutions.

Persona (Choosing Your AI Chef): Tell the AI who to act as or who the target audience is. Do you want it to sound like a witty marketer, a formal business consultant, or a supportive coach? Defining a persona helps the AI adopt the right tone and style, enhancing the quality of AI-generated content.

Format (Plating Instructions): Specify the desired output structure. Do you need a bulleted list, a paragraph, a table, an email, or even a JSON object? This ensures you get the information in the most useful way, making AI for productivity truly impactful.

By combining these four elements, you transform AI from a generic tool into a highly effective, personalized assistant for digital transformation.

AI for Work Efficiency: Automate, Accelerate, Achieve with AI Tools

Well-crafted AI prompts are your key to saving countless hours and boosting business productivity. Here’s how AI, guided by your precise instructions, can streamline your work processes:

Automate Repetitive Tasks: Need to draft a promotional email, generate social media captions, or outline a simple business plan? Instead of starting from scratch, a clear AI prompt can give you a high-quality first draft in minutes. This frees you from mundane tasks, allowing you to focus on AI strategy and human connection.

Generate Ideas & Summarize Information: Facing writer’s block for a blog post series? Need to quickly grasp the key takeaways from a long market report? AI tools can brainstorm diverse ideas or condense lengthy texts into digestible summaries, accelerating your research and content creation efforts.

Streamline Communication: From crafting polite cold outreach emails to preparing for challenging conversations with employees, AI can help you structure your thoughts and draft professional messages, ensuring clarity and impact across your business operations.

The power lies in your ability to instruct. The more precise your “recipe,” the more efficient your “AI chef” becomes, driving business automation and operational excellence.

AI for Enhanced Learning: Grow Your Skills, Faster with AI

Beyond daily tasks, AI is a phenomenal tool for continuous learning and competence development. It’s like having a personalized tutor and research assistant at your fingertips:

Identify Key Skills: Whether you’re looking to upskill for a new role or identify crucial competencies for an upcoming project, AI can generate lists of essential hard and soft skills, complete with explanations of their importance for professional development.

Outline Learning Plans: Want to master a new software or understand a complex methodology? Provide AI with your current familiarity, time commitment, and desired proficiency, and it can outline a structured learning plan with weekly objectives and suggested resources for AI-powered learning.

Generate Training Topics: For team leads, AI can brainstorm relevant and engaging topics for quick team training sessions, addressing common challenges or skill gaps. This makes professional development accessible and timely.

Structure Feedback: Learning and growth are fueled by feedback. AI can help you draft frameworks for giving and receiving constructive feedback, making these conversations more productive and less daunting.

AI empowers you to take control of your learning, making it more targeted, efficient, and personalized than ever before.

Your AI Kitchen Rules: Cook Smart, Cook Ethically

As you embrace AI in your daily operations and learning, remember these crucial “kitchen rules” from the “AI Cookbook”:

Always Review and Refine: AI-generated content is a fantastic starting point, but it’s rarely perfect. Always review, edit, and add your unique human touch and expertise. You’re the head chef!

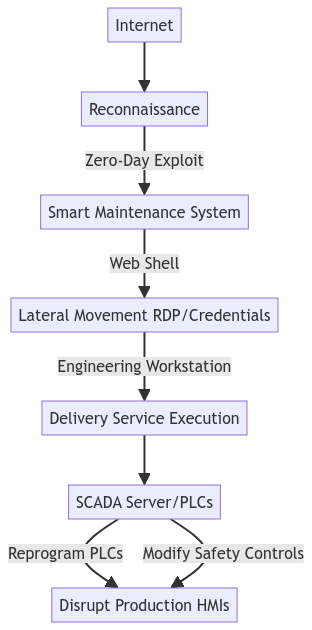

Ethical Considerations: Be mindful of how you use AI. Respect privacy, avoid plagiarism (cite sources if AI helps with research that you then use), and ensure your AI-assisted communications are honest and transparent. For a deeper dive into potential risks, especially concerning AI agents and cybersecurity pitfalls, you might find this article insightful: AI Agents and Cybersecurity Pitfalls. Never input sensitive personal or financial data into public AI tools unless you are certain of their security protocols and terms of service.

Keep Experimenting: The world of AI is evolving at lightning speed. Stay curious, keep trying new prompts, and adapt the “recipes” to your specific needs. The more you “cook” with AI, the better you’ll become at it.

The future of business is undoubtedly intertwined with Artificial Intelligence. By embracing AI as a collaborative tool, you can free up valuable time, automate mundane tasks, spark new ideas, and ultimately focus on what you do best – building and growing your business and yourself.

So, don’t be afraid to get creative in your AI kitchen, and get ready to whip up some amazing results. Your AI-powered business future is bright!

Ready to master your AI kitchen? Unlock even more powerful “recipes” and transform your business today! Get your copy of the full AI Prompt Cookbook here: Master Your AI Kitchen!

Transparency; AI helped write this post.