It was a crisp summer Monday, and Alex, the maintenance engineer at Pulp Friction Paper Company, arrived with his coffee, ready to tackle the day. He reveled in the production regularity achieved thanks to his recently implemented smart maintenance program. This program used machine learning to anticipate condition degradation in machinery, a significant improvement over the facility’s previous reliance on traditional periodic maintenance or the ineffective risk-based approaches.

Alex, a veteran at Pulp Friction, had witnessed the past struggles. Previously, paper products were frequently rejected due to inconsistencies in humidity control, uneven drying, or even mechanical ruptures. He was a firm believer in leveraging modern technology, specifically AI, to optimize factory operations. While not a cybersecurity expert, his awareness wasn’t limited to just using technology. He’d read about the concerning OT (Operational Technology) attacks in Denmark last year, highlighting the inherent risks of interconnected systems.

As a seasoned maintenance professional, Alex understood the importance of anticipating breakdowns for effective mitigation. He empathized with the security team’s constant vigilance against zero-day attacks – those unpredictable, catastrophic failures that could turn a smooth operation into a major incident overnight.

Doctors analysing micro blood samples on advanced chromatographic paper form

Pulp Friction Paper Mills

Dark clouds over Pulp Friction

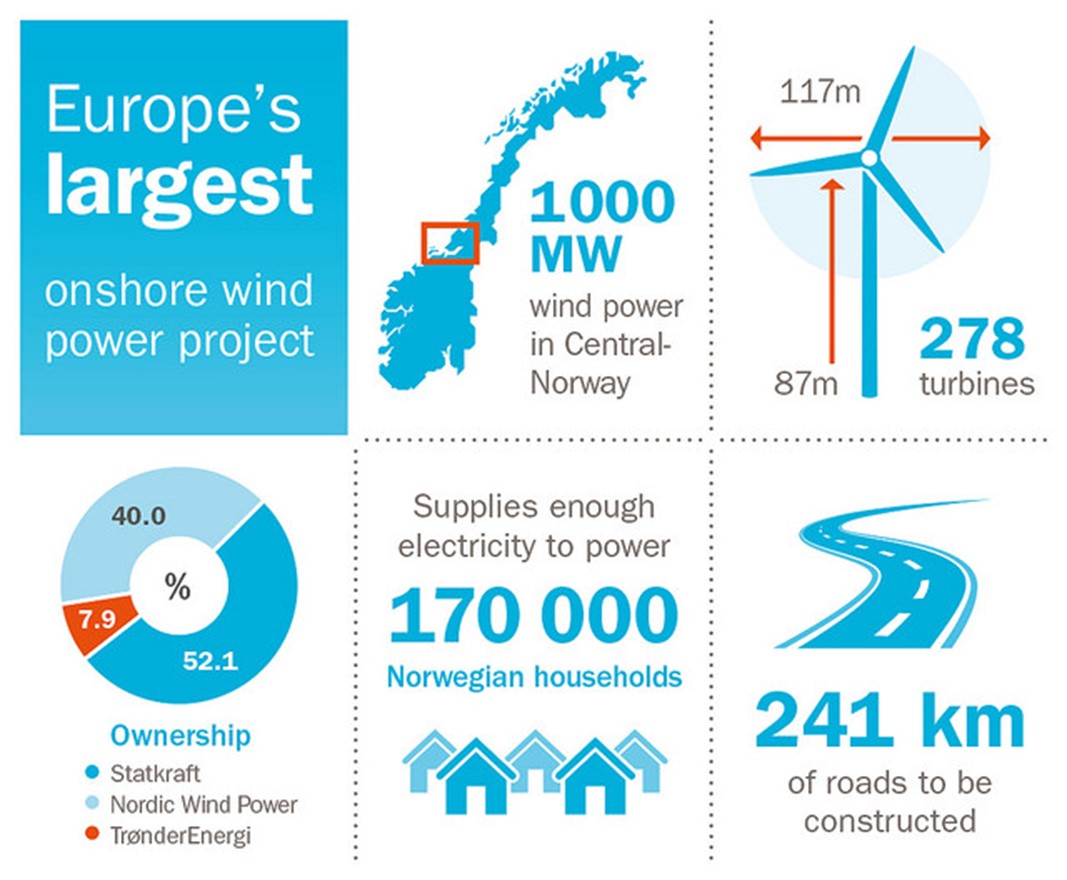

A digital phantom stalked the web. “The Harvester,” a notorious APT (Advanced Persistent Threat) group known for targeting high-value assets, had Pulp Friction Paper Company in their crosshairs. Their prize? Not paper, but a revolutionary innovation: medical diagnostic paper. Pulp Friction had recently begun producing these specialized sheets, embedded with advanced materials, for use in chromatographic tests. This cutting-edge technology promised rapid diagnosis of a multitude of diseases from mere microliter blood samples, a potential game-changer in the medical field. Unbeknownst to Alex, a gaping zero-day vulnerability resided within the facility’s industrial control system (ICS) software. If exploited, The Harvester could wreak havoc, disrupting production of these life-saving diagnostic tools and potentially delaying critical medical care for countless individuals. The stakes had just been raised. Could Alex, with his limited cybersecurity awareness, and the current defenses, thwart this invisible threat and ensure the smooth flow of this vital medical technology?

A wave of unease washed over Alex as he stared at the malfunctioning control panel. The usually predictable hum of the paper production line had been replaced by a cacophony of alarms and erratic readings. Panic gnawed at him as vital indicators for the chromatographic test paper production process lurched erratically. This wasn’t a typical equipment malfunction – it felt deliberate, almost malicious.

Just then, a memory flickered in Alex’s mind. Sarah, the friendly and highly skilled network security specialist he occasionally consulted with, had been pushing for a new security system called “zero-trust.” While Alex appreciated Sarah’s expertise, he hadn’t quite understood the nuances of the system or its potential benefits. He’d brushed it off as an extra layer of complexity for an already demanding job.

Now, regret gnawed at him alongside the growing sense of dread. Grabbing his phone, Alex dialed Sarah’s number, his voice laced with a tremor as he blurted out, “Sarah, something’s terribly wrong with the ICS system! The readings are all messed up, and I don’t know what’s happening!” The urgency in his voice was impossible to miss, and Sarah, sensing the dire situation, promised to be there as soon as possible. With a heavy heart, Alex hung up, the echo of his own ignorance a stark reminder of the consequences he might have inadvertently unleashed by ignoring the recommendations on network security improvements.

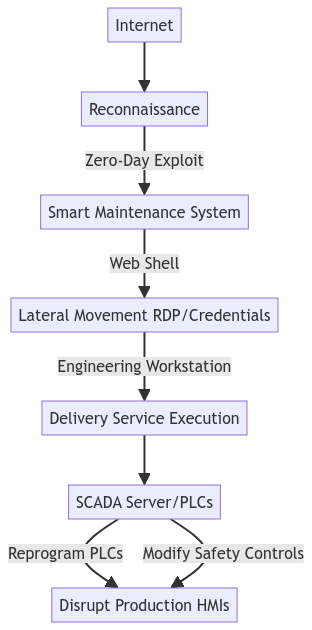

The Harvester: a technical intermezzo

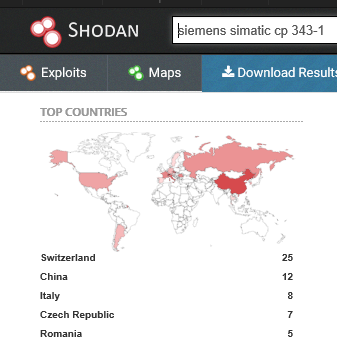

The Harvester is capable of zero-day research and exploit development. In this attack they are targeting companies using advanced technologies to supply to healthcare providers – and many of those companies use innovative maintenance systems.

They first find a web exposed server used by the AI driven maintenance system. The system is Internet exposed due to frequent need for access by multiple vendors. By exploiting the vulnerability there, they gain root access to the underlying Linux operating system. The Harvester, like many other threat actors, then install a web shell for convenient persistent access, and continue to move on using conventional techniques. Reaching the engineering workstation, the attacker is able to reprogram PLC’s, and disable safety features. Having achieved this, the system is no longer a highly reliable production system for diagnostic test paper: it is a bleeping mess spilling water, breaking paper lines and causing a difficult-to-fix mess.

They continue to pose as Pulp Friction employees, leaking CCTV footage of the mess on the factory floor, showing panicking employees running around, and also post on social media claiming Pulp Friction never cared about reliability or security, and that money was the only goal, without any regard for patient safety: this company should never be allowed to supply anything to hospitals or care providers!

Enjoying the post? Subscribe to get the next one delivered to your inbox!

What it took to get back to business

Sarah arrived at Pulp Friction, a whirlwind of focused energy. Immediately, she connected with Alex and reviewed the abnormal system behavior. Her sharp eyes landed on the internet access logs for the smart maintenance system – a system Alex had mentioned implementing. Bingo! This web-exposed system, likely the initial point of entry, was wide open to the internet. Without hesitation, Sarah instructed the IT team to isolate and disable the internet access for the maintenance system – a crucial first step in stemming the bleeding.

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.”

Edmund Burke

Cybersecurity meaning: “Don’t be a sitting duck the day the zero-day is discovered.”

Next, she initiated the full incident response protocol, securing compromised systems, isolating affected network segments, and reaching out to both the Pulp Friction IT team and external forensics experts. The following 48 hours were a blur – a symphony of collaboration. Sarah led the incident response, directing forensics on evidence collection and containment, while the IT team worked feverishly to restore services and patch vulnerabilities.

Exhausted but resolute, Sarah and Alex presented their findings to the CEO. The CEO, witnessing the team’s dedication and the potential consequences, readily approved Sarah’s plan for comprehensive security improvements, including implementing zero-trust and segmentation on the OT network, finally putting Pulp Friction on the path to a more robust defense. They couldn’t erase the attack, but they could ensure it wouldn’t happen again.

With the immediate crisis averted, Sarah knew a stronger defense was needed. She turned to Alex, his eyes reflecting a newfound appreciation for cybersecurity. “Remember zero-trust, Alex? The system I’ve been recommending?” Alex nodded, his earlier skepticism replaced by a desire to understand.

“Think of it like guarding a high-security building,” Sarah began. “No one gets in automatically, not even the janitor. Everyone, from the CEO to the maintenance crew, has to show proper ID and get verified every time they enter.”

Alex’s eyes lit up. “So, even if someone snuck in through a hidden door (like the zero-day), they wouldn’t have access to everything?”

“Exactly!” Sarah confirmed. “Zero-trust constantly checks everyone’s access, isolating any compromised systems. Imagine the attacker getting stuck in the janitor’s closet, unable to reach the control room.”

Alex leaned back, a relieved smile spreading across his face. “So, with zero-trust, even if they got in through that maintenance system, they wouldn’t be able to mess with the paper production?”

“Precisely,” Sarah said. “Zero-trust would limit their access to the compromised system itself, preventing them from reaching critical control systems or causing widespread disruption.”

With the analogy clicking, Alex was on board. Together, Sarah and Alex presented the zero-trust solution to the CEO, emphasizing not only the recent attack but also the potential future savings and improved operational efficiency. Impressed by their teamwork and Sarah’s clear explanation, the CEO readily approved the implementation of zero-trust and segmentation within the OT network.

Pulp Friction, once vulnerable, was now on the path to a fortress-like defense. The zero-day vulnerability might have been a wake-up call, but with Sarah’s expertise and Alex’s newfound understanding, they had turned a potential disaster into a catalyst for a much stronger security posture. As production hummed back to life, creating the life-saving diagnostic paper, a sense of quiet satisfaction settled in. They couldn’t erase the attack, but they had ensured it wouldn’t happen again.

How Alex and Sarah collaborated to achieve zero-trust benefits in the OT network

Zero-trust in the IT world relies a lot on identity and endpoint security posture. Both those concepts can be hard to implement in an OT system. This does not mean that zero-trust concepts have no place in industrial control systems, it just means that we have to play within the constraints of the system.

- Network segregation is critical. Upgrading from old firewalls to modern firewalls with strong security features is a big win.

- Use smaller security zones than what has been traditionally accepted

- For Windows systems in the factory, on Layer 3 and the DMZ (3.5) in the Purdue model, we are primarily dealing with IT systems. Apply strong identity controls, and make patchable systems. The excuse is often that systems cannot be patched because we allow no downtime, but virtualization and modern resilient architectures allow us to do workload management and zero-downtime patching. But we need to plan for it!

- For any systems with weak security features, compensate with improved observability

- Finally, don’t expose things to the Internet. Secure your edge devices, use DMZ’s, VPN’s, and privileged access management (PAM) systems with temporary credentials.

- Don’t run things as root/administrator. You almost never need to.

In a system designed like this, the maintenance server would not be Internet exposed. The Harvester would have to go through a lot of hoops to land on it with the exploit. Assuming the threat actor manages to do that through social engineering and multiple hops of lateral movement, it would still be very difficult to move on from there:

- The application isn’t running as root anymore – only non-privileged access

- The server is likely placed in its own information management zone, receiving data through a proxy or some push/pull data historian system. Lateral movement will be blocked on the firewall, or at least require a hard-to-configure bypass.

- The engineering workstations are isolated and not network reachable without a change request for firewall rules. Getting to the place the settings and logic can be changed gets difficult.

- The PLC’s are configured to not be remotely programmable without a physical change (like a physical key controlling the update mode).

Using Sarah’s plan, the next time The Harvester comes along, the bad guy is turned away at the door, or gets locked into the janitor’s closet. The diagnostic paper is getting shipped.

Key take-aways:

- Exposing critical systems directly on the Internet is not a good idea, unless it is meant to be a web service engineered for that type of hostile environment

- Zero-trust in OT systems is possible, and is a good strategy to defend against zero-days.

- Defenders must be right all the time, hackers only need to get lucky once is a lie – if you implement good security architecture. Lucky once = locked into the janitor’s closet.