This week we celebrated the “Sikkerhetsfestivalen” or the “Security Festival” in Norway. This is a big conference trying to combine the feel of a music festival with cybersecurity talks and demos. I gave a talk on how the attack surface expands when we connect OT systems to the cloud, and how we should collaborate between OT engineers, cloud developers and other stakeholders to do it anyway, if we want to get the benefits of cloud computing and better data access for our plants.

OT and Cloud was a popular topic by the way, several talks centered around this:

- One of the trends mentioned by Samuel Linares (Accenture) in his talk “OT: From the Field to the Boardroom: What a journey!” was the integration of cloud services in OT, and the increased demand for plant data for use in other systems (for example AI based analytics and decision support).

- A presentation by Maria Bartnes (SINTEF) about a project that SINTEF did for NVE on assessing the security and regulatory aspects of using cloud services in Class 1 and 2 control systems in the power and utility sector. The SINTEF report is open an can be read in its entirety here: https://publikasjoner.nve.no/eksternrapport/2025/eksternrapport2025_06.pdf. The key take-away form the report is that there are more challenging regulatory barriers, than chalelnges implementing secure enough solutions.

My take on this at the festival was from a more practical point of view.

(English tekst follows the Norwegian)

Sikkerhetsfestivalen 2025

Denne uka var jeg på Sikkerhetsfestivalen på Lillehammer sammen med 1400 andre cybersikkerhetsfolk. Det morsomme med denne konferansen, som tar mål av seg å være et faglig treffsted med konferansestemning, er at kvaliteten er høy, humøret er godt, og man får muligheten til å få faglig påfyll, treffe gamle kjente, og få noen nye faglige bekjentskaper på noen korte intense dager.

I år deltok jeg med et foredrag om OT og skytjenester. Stadig flere som levererer kontrollsystemer, tilbyr nå skyløsninger som integrerer med mer tradisjonelle kontrollsystemer. Det har lenge vært et tema med kulturforskjellen mellom IT-avdelingen og automasjon, men når man skal få OT-miljøer til å snakke med de som jobber med applikasjonsutvikling i skyen, får vi virkelig strekk i laget. På OT-siden ønsker vi full kontroll over endringer, og må sikre systemer som ofte har svake sikkerhetsegenskaper, men hvor angrep kan gi veldig alvorlige konsekvenser, inkludert alvorlige ulykker som kan føre til skader og dødsfall, eller store miljøutslipp. På den andre siden finner vi en kultur hvor endring er det normale, smidig utvikling står i høysetet, og man har et helt annet utvalg i verktøyskrinet for å sikre tjenestene. Skal vi få til å samarbeide her, må begge parter virkelig ville det og gjøre en innsats!

For å illustrere denne utfordringen tok jeg med meg et lite demoprosjekt, som illustrerer utviklingen fra en verden der OT-systemer opprinnelig var skjermet fra omgivelsene, til nåtiden hvor vi integrerer direkte mot skyløsninger og kan styre fysisk utstyr via smarttelefonen. Selve utformingen av denne demoen ble til som et slags hobbyprosjekt sammen med de yngste i familien i sommer: Building a boom barrier for a security conference – safecontrols.

La oss se på hvordan vi legger til stadig flere tilkoblingsmuligheter her, og hva det har å si for angrepsflaten.

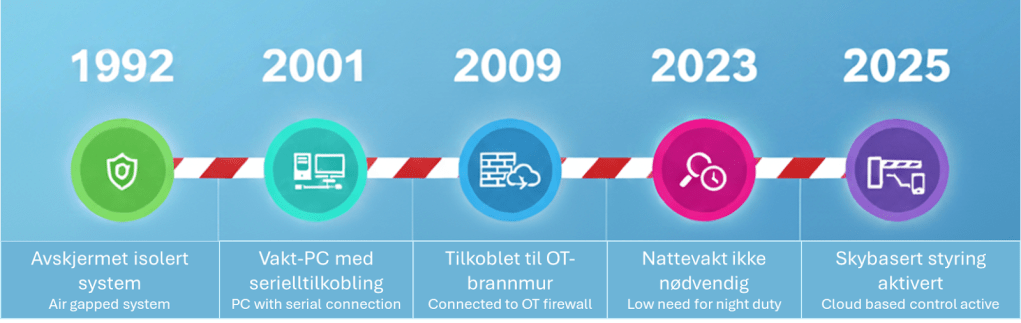

1992: Angrepsflaten er kun lokal. Det er kun en veibom med en enkel knapp for å åpne og lukke. Denne betjenes av en vakt på stedet.

2001: Vakt-PC i vaktbua, med serielltilkobling til styringsenheten på bommen. Angrepsflata er fortsatt lokal, men inkluderer nå vakt-PC. Denne er ikke koblet til eksterne nett, men det er for eksempel mulig å spleise seg inn på kabelen og sende kommandoer fra sin egen enhet til bommen om man har tilgang til den.

2009: Systemet er tilkoblet bedriftens nettverk via OT-brannmur. Dette muliggjør fjerntilgang for å hente ut logger fra kontoret, uten behov til å reise ut til hver lokasjon. Angrepsflaten er nå utvidet, med tilgang i bedriftsnettet er det nå mulig å komme seg inn i OT-nettet og fjernstyre bommen.

2023: Aktiviteten på natt er redusert, og analyser av åpningtidspunkter viser at det ikke lenger er behov for nattevakt.

2025: Skybasert styringssystem “Skybom” implementeres, og man trenger ikke lenger nattevakt. De få lastebilene som kommer på natta får tilgang, sjåførene kan selv åpne bommen via en kode på smarttelefonen. Nå er angrepsflaten videre utvidet, en angriper kan gå på programvaren som styrer systemet, sende phishing til lastebilsjåfører, bruke mobil skadevare på sjåførenes mobiler, eller angripe selve skyinfrastrukturen. Det er også en ny hardwaregateway i OT-nettet som kan ha utnyttbare sårbarheter.

I det opprinnelige systemet var de digitale sikkerhetsbehovene moderate, på grunn av veldig lav eksponering. Etter hvert som man har økt antallet tilkoblinger og integrasjoner, øker angrepsflaten, og det gjør også at sikkerhetskravene bør bli strengere. I moderne OT-nett vil man typisk bruke risikovurderinger for å sette et sikkerhetsnivå, med tilhørende krav. Den mest vanlige standarden er IEC 62443. Her skal man bryte ned OT-nettet i soner og kommunikasjonskanaler, utføre en risikovurdering av disse og sette et sikkerhetsnivå fra 1-4, hvor 1 er grunnleggende, og 4 er strenge sikkerhetskrav. Her er det kanskje naturlig å dele nettverket inn i 3 sikkerhetssoner: skysonen, nettverkssonen, og kontrollsonen.

Det finnes mange måter å vurdere risiko for et nettverk på. En svært enkel tilnærming vi kan bruke er å spørre oss 3 spørsmål om hver sone:

- Er målet attraktivt for angriperen (juicy)?

- Er målet lett å kompromittere (lav sikkerhetsmessig modenhet)?

- Er målet eksponert (feks tilgjengelig på internett)?

Jo flere “ja”, jo høyere sikkerhetskrav. Her ender vi kanskje med SL-3 for skysonen, SL-2 for lokalt nettverk, og SL-1 for kontrollsonen. Da vil vi få strenge sikkerhetskrav for skysonen, mens vi har mer moderate krav for kontrollsonen, som i større grad også lar seg oppfylle med enklere sikkerhetsmekanismer.

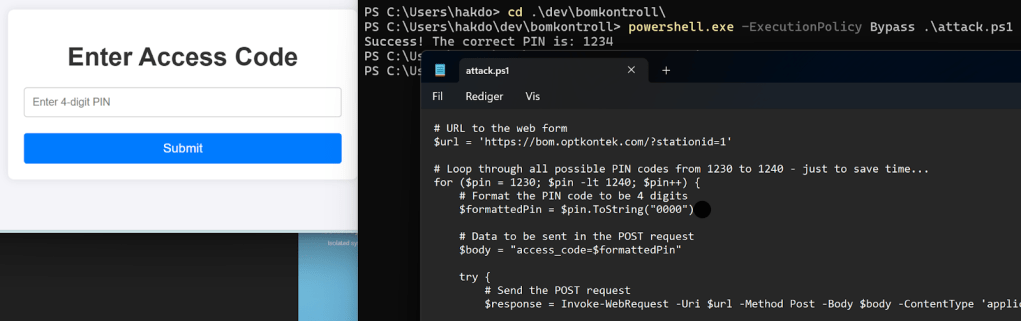

I foredraget viste jeg et eksempel vi dessverre har sett i mange reelle slike systemer: de nye skybaserte systemene er laget uten særlig tanke for sikkerhet. Det hender seg også (kanskje oftere) at systemene har gode sikkerhetsfunksjoner som må konfigureres av brukeren, men hvor dette ikke skjer. I vårt eksempel har vi en delt pinkode til bommen som alle lastebilsjåførene bruker, et system direkte eksponert på internett og ingen reell herding av systemene.Det er heller ingen overvåkning og respons. Dette gjør for eksempel at enkle brute-force-angrep er lette å gjennomføre, noe vi demonstrerte som en demo.

Til slutt så vi på hvordan vi kunne sikret systemet bedre med tettere samarbeid. Ved å inkludere skysystemet i en “skysone” og bruke SL 3 som grunnlag, ville vi for eksempel definert krav til individuelle brukerkontoer, ratebegrensning på innlogginsforsøk, bruk av tofaktorautentisering og ha overvåkning og responsevne på plass. Dette vil i stor grad redusert utfordringene med økt eksponering, og gjort det vanskeligere for en ekstern trusselaktør å lykkes med og åpne bommen via et enkelt angrep.

Vi diskuterte også hvordan vi kan bruke sikkerhetsfunksjonalitet i skyen til å bedre den totale sikkerhetstilstanden i systemet. Her kan vi for eksempel sende logger fra OT-miljøet til sky for å bruke bedre analyseplattformer, vi kan automatisere en del responser på indikatorer om økt trusselnivå før noen faktisk klarer å bryte seg inn og stjele farlige stoffer fra et lager eller liknende. Skal vi få på plass disse gode sikkerhetsgevinstene fra et skyprosjekt i OT, må vi ha tett samarbeid mellom eieren av OT-systemet, leverandørene det er snakk om, og utviklingsmiljøet. Vi må bygge tillit mellom miljøene gjennom åpenhet, og sørge for at OT-systemets behov for forutsigbarhet ikke overses, men samtidig ikke avvise gevinstene vi kan få fra bedre bruk av data og integrasjoner.

OT and Cloud Talk – in English!

This week I was at the Security Festival in Lillehammer along with 1400 other cybersecurity professionals. The great thing about this conference, which aims to be a professional meeting place with a festival atmosphere, is that the quality is high, the mood is good, and you get the opportunity to gain new technical knowledge, meet old friends, and make new professional acquaintances over a few short, intense days.

This year I participated with a presentation on OT and cloud services. More and more companies that deliver control systems are now offering cloud solutions that integrate with more traditional control systems. The cultural difference between the IT department and the automation side has long been a topic of discussion, but when you have to get OT environments to talk to those who work with application development in the cloud, you really get a stretch in the team. On the OT side, we want full control over changes and have to secure systems that often have weak security features, but where attacks can have very serious consequences, including severe accidents that can lead to injury and death, or major environmental spills. On the other hand, we find a culture where change is the norm, agile development is paramount, and there is a completely different set of tools available for securing services. If we are to collaborate here, both parties must truly want to and make an effort!

To illustrate this challenge, I brought a small demo project with me, which illustrates the development from a world where OT systems were originally isolated from their surroundings, to the present day where we integrate directly with cloud solutions and can control physical equipment via a smartphone. The design of this demo came about as a kind of hobby project with the youngest members of my family this summer: Building a boom barrier for a security conference – safecontrols.

Let’s look at how we are constantly adding more connectivity options here, and what that means for the attack surface.

1992: The attack surface is local only. It is just a boom barrier with a simple button to open and close. This is operated by an on-site guard.

2001: The guard has a PC in the guardhouse, with a serial connection to the control unit on the barrier. The attack surface is still local, but now includes the guard’s PC. This is not connected to external networks, but it is, for example, possible to splice into the cable and send commands from your own device to the barrier if you have access to it.

2009: The system is connected to the corporate network via an OT firewall. This enables remote access to retrieve logs from the office, without the need to travel to each location. The attack surface has now expanded; with access to the corporate network, it is now possible to get into the OT network and remotely control the barrier.

2023: Activity at night is reduced, and analyses of opening times show that there is no longer a need for a night watchman.

2025: A cloud-based control system “Skybom” is implemented, and a night watchman is no longer needed. The few trucks that arrive at night are granted access, and the drivers can open the barrier themselves via a code on their smartphone. Now the attack surface is further expanded; an attacker can go after the software that controls the system, send phishing emails to truck drivers, use mobile malware on the drivers’ phones, or attack the cloud infrastructure itself. There is also a new hardware gateway in the OT network that may have exploitable vulnerabilities.

In the original system, the digital security needs were moderate due to very low exposure. As the number of connections and integrations has increased, the attack surface also grows, which means that security requirements should become stricter. In modern OT networks, risk assessments are typically used to set a security level, with associated requirements. The most common standard is IEC 62443. Here, you should break down the OT network into zones and conduits, perform a risk assessment of these, and set a security level from 1-4, where 1 is basic and 4 is strict security requirements. Here, it is perhaps natural to divide the network into 3 security zones: the cloud zone, the network zone, and the control zone.

There are many ways to assess network risk. A very simple approach we can use is to ask ourselves 3 questions about each zone:

- Is the target attractive to the attacker (juicy)?

- Is the target easy to compromise (low security maturity)?

- Is the target exposed (e.g., accessible on the internet)?

The more “yeses,” the higher the security requirements. Here we might end up with SL-3 for the cloud zone, SL-2 for the local network, and SL-1 for the control zone. This would give us strict security requirements for the cloud zone, while we have more moderate requirements for the control zone, which can also be fulfilled to a greater extent with simpler security mechanisms.

In the presentation, I showed an example that we have unfortunately seen in many real systems like this: the new cloud-based systems are created with little thought for security. It also happens (perhaps more often) that the systems have good security features that must be configured by the user, but this does not happen. In our example, we have a shared PIN code for the barrier that all truck drivers use, a system directly exposed to the internet, and no real hardening of the systems. There is also no monitoring and response. This makes simple brute-force attacks easy to carry out, something we demonstrated as a demo.

Finally, we looked at how we could better secure the system with closer collaboration. By including the cloud system in a “cloud zone” and using SL 3 as a basis, we would, for example, define requirements for individual user accounts, rate limiting on login attempts, the use of two-factor authentication, and have monitoring and response in place. This would largely reduce the challenges with increased exposure and make it more difficult for an external threat actor to succeed in opening the barrier via a simple attack.

We also discussed how we can use security functionality in the cloud to improve the overall security posture of the system. For example, we can send logs from the OT environment to the cloud to use better analysis platforms, we can automate some responses to indicators of increased threat levels before someone actually manages to break in and steal dangerous substances from a warehouse or similar. To implement these good security benefits from a cloud project in OT, we must have close collaboration between the owner of the OT system, the relevant suppliers, and the development environment. We must build trust between the teams through openness and ensure that the OT system’s need for predictability is not overlooked, while at the same time not rejecting the benefits we can get from better use of data and integrations.