SCADA security has lately received lots of attention, both in mainstream media and within the security community. There are good reasons for this, as an increasing number of manufacturing and energy companies are seeing information security threats becoming more important. SANS recently issued a whitepaper on industrial control systems and security based on a survey among professionals on all continents. The whitepaper contains many interesting results from the survey. These are three of the most interesting findings:

- 15% of respondents who had identified security breaches found that current contractors, consultants or suppliers were responsible for the breach

- Only 35% of respondents actively include security requirements in their purchasing process

- The number of breaches in industrial control systems seem to be increasing (9% of respondents had identified such breaches in the 2014 survey vs. 17% in the 2015 survey)

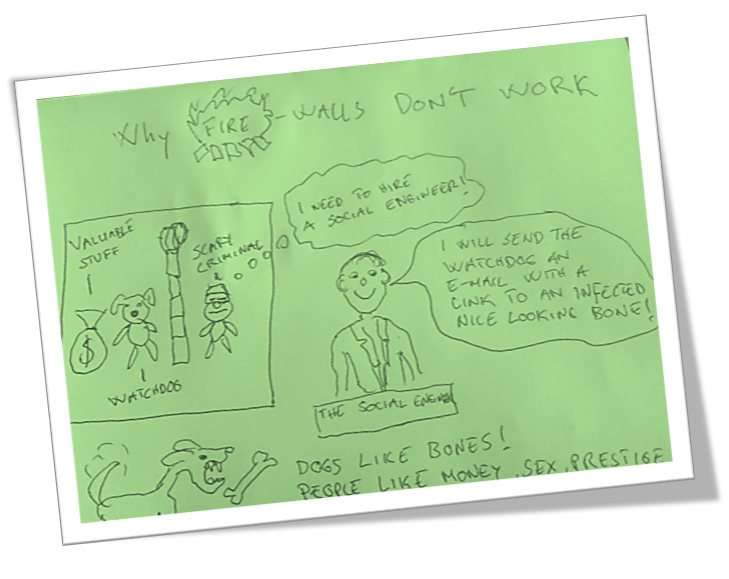

That external parties with legitimate access to the SCADA networks are sources in many actual breaches is not very surprising. These parties are normally outside the asset owner’s management control, and they may have very different policies, awareness and protections available at their end. One notable example from a while back where this was the case in a much publicized data breach was the Target fraud in 2014. In that case, the attack vector came via a phishing e-mail sent to representatives for one of Target’s HVAC vendors. The vendor connected to Target’s IT network over a VPN tunnel, unknowingly transporting the malware to the network. The advanced attack managed to siphon away credit card data from millions of customers, uploading it to an FTP server located in Russia. Media has described this attack in detail and from many angles and it is an interesting case study on advanced persistent threats.

This is obviously a cause of concern; how do you protect yourself against attack vectors using your vendors as point of entry? Of course, managing credentials and only giving access to systems the vendor should have access to is a good starting point. But what can you do to influence whaty they do on “the other side” of the contract interface?

First of all – security awareness training should not only be for engineers and operators. The same type of awareness training and understanding of the business risk related to cyber attacks should be provided to your purchasers. From reliability engineering we have long seen that obtaining items that comply with requirements can be challenging; if the requirements are not even articulated, no compliance can be expected. Including security requirements in purchasing and contracts should be an important priority. It is probably a good idea to include this in your company’s security policy.

The next obvious question is maybe “what kind of requirements should I put forward to the vendor”? This depends on your situation and the risk to your assets, but it should include both technology requirements, after-sales updating and service requirements, security practices, and awareness requirements for companies providing services. If your HVAC vendor has low security awareness, it is more likely that he or she will fall for a phishing attempt – putting your control system assets at risk. Due diligence should thus include cyber security requirements; it is really no different from other quality and risk management controls that we normally integrate into our purchasing processes.